The Battle of Getlin’s Corner

FORWARD

by

General Richard I. Neal, USMC (Ret.)

Assistant Commandant

United States Marine Corps

For some, the measure of a battle is the number of casualties, the enemy body count, the duration of the fight, and the awards earned. To those who fought in such conflicts, those metrics do not truly capture or reflect the actions of those who gave their all for their fellow Marine or Sailor.

Wars fought on a grand scale with global consequences, are made up of countless smaller battles and events. For the men who fought, bled and died in them they are not small—those little pieces of war—and the personal aftermath and their effect is beyond measure.

Instead, as you will see in the narrative that follows, the true measure of a battle is the Marines and Sailors who act with uncommon valor. Such is the case of the men of India Company, Third Battalion, Ninth Marines during the horrific Battle of Getlin’s Corner on 30-31 March 1967 where and when uncommon valor was a common virtue.

For this reason, the Getlin Corner Foundation was established, simply to recognize how proud we are of every Marine and Sailor involved in the battle. And to ensure their efforts and sacrifices are not forgotten through this Foundation and the scholarships provided to worthwhile and deserving young men and women.

BATTLEFIELD STUDY: I/3/9 at Getlin’s Corner in 1967

by Michael F. McNamara | May 9, 2018 | Battlefield Study, Combat, Leadership, Medal of Honor, Vietnam

The Battle of Getlin’s Corner

For the Marines of India Company, 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines, dawn in Vietnam on the morning of 30 March 1967 broke more like a typical mid-summer’s day, even though it was early spring.

The heat and humidity would be stifling. Water would be scarce. Heat stroke was a distinct possibility. If for no other reason, the company was facing some long and difficult hours as the sun rose on the morning of 30 March 1967. But the weather would be the least of the Marines’ challenges on that day.

The heat and humidity would be stifling. Water would be scarce. Heat stroke was a distinct possibility. If for no other reason, the company was facing some long and difficult hours as the sun rose on the morning of 30 March 1967. But the weather would be the least of the Marines’ challenges on that day.

Two days earlier, the company commander gathered his officers for a briefing on the orders he had just received from the battalion headquarters. The 220-man company, known as “The Flaming I”, was going to participate in Operation Prairie III, which would be conducted in the fiercely contested territory near the DMZ, the border region that separated North from South Vietnam. The orders were for the company to move in full strength during the day, establish a company command post (CP) in the late afternoon, and then disperse its individual rifle platoons to establish night ambush sites.

These tactics were typical of how the Marine Corps operated throughout most of the war in Vietnam. There was nothing typical, however, about the tactical situation India Company faced as the day unfolded, and the company commander knew it. Earlier in the month, other Marine units had been mauled in fierce fighting against North Vietnamese Army (NVA) battalions that were determined to destroy any Marine forces they encountered. A highly experienced combat officer by this point in his Vietnam tour of duty, Captain Mike Getlin (Navy Cross) was certain that his company would engage a superior enemy force at some point during the operation. Getlin was so concerned that he argued profusely with his battalion superiors that splitting the company to establish night ambushes placed the entire company in serious jeopardy.

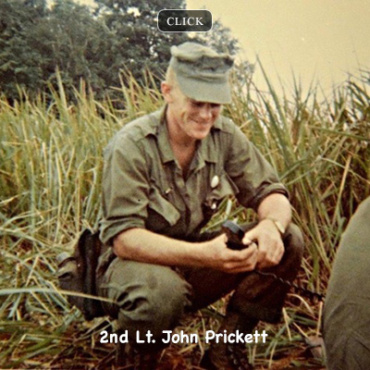

In briefing his officers prior to the operation, Captain Getlin made it clear that he expected heavy enemy contact. In fact, he took the unusual precaution of designating the chain of command should he be wounded or killed. The three rifle platoon commanders—Lieutenants John Prickett commanding the 1st platoon, Dan Pultz the second, and Ray Gaul the third—understood the risk inherent with night ambush sights in such a hostile environment, and they all shared Captain Getlin’s concern. They also understood that orders are to be followed.

But as the morning of the 30th wore on, the Marines encountered frequent and alarming signs that the enemy was close at hand: a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) launcher with its ammunition at the ready was found along an old tank trail; fresh footprints in a stream-bed; the distinctive smell of marijuana or hashish. NVA scouts were even sighted tracking the company’s movements throughout the day.

But as the morning of the 30th wore on, the Marines encountered frequent and alarming signs that the enemy was close at hand: a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) launcher with its ammunition at the ready was found along an old tank trail; fresh footprints in a stream-bed; the distinctive smell of marijuana or hashish. NVA scouts were even sighted tracking the company’s movements throughout the day.

At about 2:00 in the afternoon, the company established its command post on the reverse slope of Hill 70, which was less a hill than a slight, finger-shaped rise in elevation. Before deploying the platoons to their assigned ambush sites, Captain Getlin made a final attempt to persuade battalion leadership to allow the company to remain in tact rather than split into platoon-sized units. The exchange was brief but heated. It ended abruptly when the captain was told to either follow orders or be immediately relieved of command.

The stage was now set, and with his superiors’ refusal to allow the company to remain in tact, Getlin called his platoon commanders forward for a briefing. By 2:30, the platoons were headed out to their assigned ambush sites.

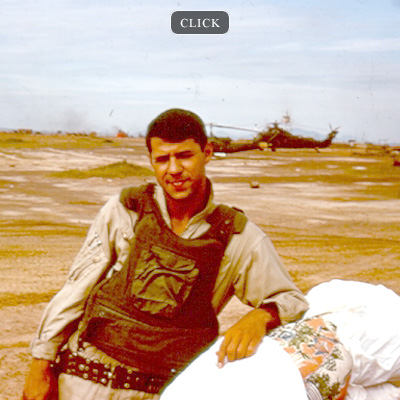

Lt. Prickett, along with Lt. Richard “Butch” Neal (Silver Star) and his Artillery Forward Observer Team, set out to establish their position just over 1,000 meters to the west of the CP. Neal was assigned to Lt. Prickett’s platoon, because the company commander thought that Prickett’s 1st platoon was most likely to come into contact with the enemy, and the captain wanted to ensure that Prickett would have immediate access to the artillery support that Lt. Neal could coordinate.

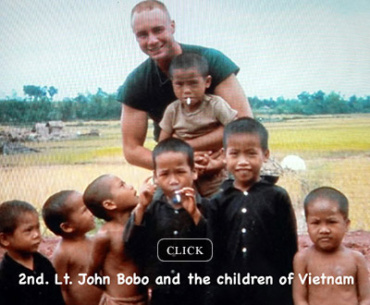

Lt. Pultz, with a reinforced squad from his 2nd platoon, which was led by Corporal Roger Turnquist, was ordered to set up an ambush site at a trail junction between Prickett’s platoon and the CP. Should the NVA decide to attack the CP, attacking through the trail junction was a probability. Lt. Gaul’s 3rd platoon established its position some 900 meters to the east of the CP. The small company command post was defended by the remaining two squads from of Lt. Pultz’s 2nd platoon. Also providing defense for the CP was the remaining 60mm mortar section, one rocket team, and one machine gun team from Lt. Bobo’s (Medal of Honor) weapons platoon. Also attached to the CP was the Forward Air Control team commanded by Marine aviator, Captain Ralph Pappas. The company was now spread along a 2,000 meter line; the CP consisted of fewer than 40 Marines.

Lt. Pultz, with a reinforced squad from his 2nd platoon, which was led by Corporal Roger Turnquist, was ordered to set up an ambush site at a trail junction between Prickett’s platoon and the CP. Should the NVA decide to attack the CP, attacking through the trail junction was a probability. Lt. Gaul’s 3rd platoon established its position some 900 meters to the east of the CP. The small company command post was defended by the remaining two squads from of Lt. Pultz’s 2nd platoon. Also providing defense for the CP was the remaining 60mm mortar section, one rocket team, and one machine gun team from Lt. Bobo’s (Medal of Honor) weapons platoon. Also attached to the CP was the Forward Air Control team commanded by Marine aviator, Captain Ralph Pappas. The company was now spread along a 2,000 meter line; the CP consisted of fewer than 40 Marines.

The battle broke out around 3:00 PM when Marines in the CP spotted two NVA soldiers walking casually near a bomb crater to the south of Hill 70. When the Marines called for them to drop their weapons, they refused and were immediately killed. Although those two soldiers were obviously no threat to the CP, no more than two or three minutes later the Marines heard the instantly recognizable sound of mortar rounds dropping into their mortar tubes. As the mortars began to rain down on Hill 70, the Marines also began to take machine gun fire; it was light at first, but quickly intensified. As the the mortar rounds began to impact the CP, the NVA mounted the first of their determined ground attacks. As the enemy soldiers charged across the field to the north of the CP, the Marines exacted a heavy price on the attackers. In addition, their assault was made all the more difficult because they were being killed by their own mortar rounds as they moved across the open terrain.

When Lieutenants Prickett and Gaul heard the mortar fire, they each immediately radioed Captain Getlin to ask if the CP needed help. With Marine fire devastating the ranks of the charging NVA, the captain and his Company First Sergeant, Ray Rogers (Navy Cross), believed that the situation was under control, and Getlin ordered the platoon commanders to hold their positions for the time being.

Within minutes, however, the full force of an NVA battalion descended upon the CP in a massive ground attack across the open field to the north. The Marines suddenly found themselves opposed by 700-800 soldiers armed with wheeled machine guns and heavy mortars. The NVA were prepared to suffer heavy casualties in their attack; their soldiers wore cloth tourniquets around their upper arms and thighs so they could quickly stem the bleeding should they be seriously wounded. Many also had a noose around their ankle so that a rope could be passed through it to drag the soldier from the battlefield if he became incapacitated.

Within minutes, however, the full force of an NVA battalion descended upon the CP in a massive ground attack across the open field to the north. The Marines suddenly found themselves opposed by 700-800 soldiers armed with wheeled machine guns and heavy mortars. The NVA were prepared to suffer heavy casualties in their attack; their soldiers wore cloth tourniquets around their upper arms and thighs so they could quickly stem the bleeding should they be seriously wounded. Many also had a noose around their ankle so that a rope could be passed through it to drag the soldier from the battlefield if he became incapacitated.

As it became apparent to Captain Getlin that his CP was under a major attack, he radioed Lt. Neal with instructions to, “Give us everything you have.” When Lt. Neal realized and advised his company commander that the grid coordinates given by the captain would bring artillery fire directly upon the CP, Captain Getlin confirmed the fire mission, informing Neal that the NVA were already within the Marines’ perimeter. The situation had quickly deteriorated to desperate!

First Sergeant Ray “Top” Rogers was alongside Captain Getlin when the fighting began, and he later recalled: “We thought we had it under control. But suddenly the NVA was everywhere! They were all around us, even in the trees! It was worse than the Chosin!” (1st. Sgt. Rogers fought in the infamous Korean War Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. He was one of just 36 Marines from his company of 220 men to survive the battle.)

The fiercest fighting took place in just the first 2-3 hours of the battle, and while the focus was primarily on the CP atop Hill 70, the 1st. and 3rd. platoons were also heavily engaged as they attempted to fight their was back to rescue the CP. Corporal Jack Riley’s squad of the 2nd platoon was defending the north side of Hill 70 and took the brunt of the NVA assault. Riley (Silver Star) could see three, wheeled NVA machine guns raking the Marine positions. Collecting three Light Antitank Assault Weapons (LAAW) from his squad, the corporal personally took out all three of the crew-served guns by killing the NVA soldiers who were manning them. The machine guns themselves were not destroyed, however, and when the NVA replaced the crews that he had killed, Corporal Riley again destroyed all three gun crews with his M-79 grenade launcher.

With their intense focus on the CP Marines, the NVA were apparently unaware that Lt. Gaul’s third platoon, which was located to the east of the CP and on the left flank of the NVA attack. Shortly after the fighting began and Getlin ordered Pricket and Gaul to remain in position, the captain issued new and urgent orders to his platoon commanders. Lt. Gaul was ordered to attack the NVA on an azimuth of 270 degrees. (Gaul would later recall, “I took out my compass and checked—the Skipper was right on!”) Just as though it were a training exercise, the lieutenant put his Marines on line and began their attack on the NVA’s left flank. The thick brush and tall grass made command and control of the platoon nearly impossible, and many Marines in the 3rd. platoon had to use their own judgment and initiative throughout the attack. When their advance brought them in view of the CP, PFC Gene Chamberlain (Silver Star) could see that the Marines in the CP were engaged in hand-to-hand combat.

With their intense focus on the CP Marines, the NVA were apparently unaware that Lt. Gaul’s third platoon, which was located to the east of the CP and on the left flank of the NVA attack. Shortly after the fighting began and Getlin ordered Pricket and Gaul to remain in position, the captain issued new and urgent orders to his platoon commanders. Lt. Gaul was ordered to attack the NVA on an azimuth of 270 degrees. (Gaul would later recall, “I took out my compass and checked—the Skipper was right on!”) Just as though it were a training exercise, the lieutenant put his Marines on line and began their attack on the NVA’s left flank. The thick brush and tall grass made command and control of the platoon nearly impossible, and many Marines in the 3rd. platoon had to use their own judgment and initiative throughout the attack. When their advance brought them in view of the CP, PFC Gene Chamberlain (Silver Star) could see that the Marines in the CP were engaged in hand-to-hand combat.

When Chamberlain’s fire team leader was killed, the young Private First Class assumed command of the fire team just as the NVA mounted a fierce attack on the 3rd. platoon’s flank. Although wounded in the head, arm, leg, and chest, Chamberlain and the two Marines on his team—neither of whom had any combat experience— successfully broke the enemy attack and kept the NVA from rolling up the 3rd platoon’s flank.

Back on the top of Hill 70, Captain Getlin and all three of the radiomen who were with him were wounded in the initial attack. While continuing to fire his shotgun into the advancing enemy, Getlin pulled his wounded radiomen close to him where he could provide some protection. He continued to fire his shotgun at such a rapid rate that the barrel peeled back like the skin of a banana. Top Rogers, seeing the damage to the weapon, cried out to the captain, “Skipper, you can’t keep shooting that thing!” Captain Getlin yelled back, “The hell I can’t!” When the enemy pelted his position with hand grenades, the captain hurled several back into the face of the advancing enemy. Ultimately, he was overwhelmed and killed by a fusillade of machine gun fire and grenades. Six NVA soldiers were brought down by his shattered shotgun.

Meanwhile, on the northern slope of Hill 70, the fighting was close-in, nose-to-nose. Captain Pappas was killed as he attempted to call in airstrikes. Corporal John Loweranitis (Navy Cross), who had already received the Silver Star for previous heroism, reorganized a Marine 60mm mortar position to deliver devastating fire into the attacking NVA soldiers. When mortar ammunition ran out, he moved about the hill pulling Marines to cover while continuing to deliver automatic rifle fire into the advancing enemy, killing at least five of them. With multiple shrapnel and gunshot wounds, he continuously refused evacuation. Laweranitis was finally cut down while mounting a desperate, one-man attack on an NVA machine gun position. When the courageous young Marine was found the following morning, there was not a single round left in his weapon.

Meanwhile, on the northern slope of Hill 70, the fighting was close-in, nose-to-nose. Captain Pappas was killed as he attempted to call in airstrikes. Corporal John Loweranitis (Navy Cross), who had already received the Silver Star for previous heroism, reorganized a Marine 60mm mortar position to deliver devastating fire into the attacking NVA soldiers. When mortar ammunition ran out, he moved about the hill pulling Marines to cover while continuing to deliver automatic rifle fire into the advancing enemy, killing at least five of them. With multiple shrapnel and gunshot wounds, he continuously refused evacuation. Laweranitis was finally cut down while mounting a desperate, one-man attack on an NVA machine gun position. When the courageous young Marine was found the following morning, there was not a single round left in his weapon.

The CP had a single M-60 machine gun team under the command of L/Cpl. Tom Butt (Silver Star). Other team members were Sam Phillips, Joe Lempa, and Billy Hill. Because the team was delivering deadly fire into the enemy ranks, they were a priority target for the NVA’s rocket propelled grenade (RPG) teams. Under heavy RPG fire, L/Cpl. Butt skillfully and continuously maneuver his machine gun team about the battlefield, exacting tremendous casualties among the attacking forces.

PFC Bill Stankowski (Silver Star) was another of the Marines who distinguished himself by delivering accurate and devastating rocket fire into the enemy forces. In spite of being wounded three times, Stankowski lead a small team of Marines across the fire-swept hillside in an attempt to rescue Lt. Bobo who had been seriously wounded by an enemy mortar round.

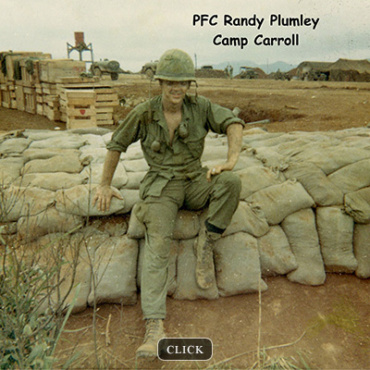

As the battle raged back and forth in the tall grass on the forward slope of the hill, Lance Corporal Randy Plumley quickly found himself an unwilling spectator for most of the battle. When his position was overrun, Plumley was captured, hog-tied, and put under the guard of an NVA soldier right in the very middle of the attack. The NVA were apparently so confident of their victory that they took captives during the battle, a practice that was extremely unusual at any time during the war in Vietnam.

As the battle lines ebbed and flowed across the north slope of Hill 70, L/Cpl. Plumley could only watch the heavy exchange of hand grenades flying over his head. Suddenly, he recalled, he saw a Marine entrenching tool (shovel) fly overhead at the NVA troops. Obviously, the Martines were in a dire position.

As the battle lines ebbed and flowed across the north slope of Hill 70, L/Cpl. Plumley could only watch the heavy exchange of hand grenades flying over his head. Suddenly, he recalled, he saw a Marine entrenching tool (shovel) fly overhead at the NVA troops. Obviously, the Martines were in a dire position.

As the battle raged, Petty Officer Ken Braun (Navy Cross) was busy demonstrating precisely why Marine infantrymen love Navy Corpsmen. Throughout the battle, and though suffering from severe shrapnel wounds early on, Doc Braun moved over the entire battlefield, pulling Marines to safety and administering to their wounds. But tending to the wounded didn’t keep Doc from exacting his own personal toll on the enemy with a malfunctioning, M-14 rifle he had picked up on the battlefield. In order to fire a single shot at a time, Doc Braun had to put the butt of the rifle against the ground to kick the bolt with his foot in order to eject the spent cartridge and chamber a new round. He killed two enemy soldiers with his damaged weapon while caring for at least 30 wounded Marines during the battle.

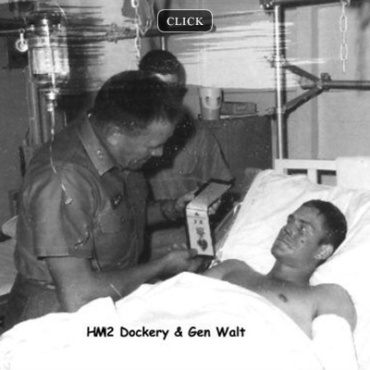

HN2 Charles Dockery was another Navy Corpsman whose courage and devotion to duty were extraordinary throughout the battle. While Doc Braun attended to the wounded on the forward slope of the hill, Doc Dockery did the same on the reverse slope. Wounded by grenade and mortar shrapnel (and shot 6 different times!) Doc Dockery never rested. When the Marines finally consolidated in their last-stand position—and in spite of the wounds that would result in the loss of both legs—Dockery insisted on being placed next to a wounded Marine who needed his medical attention. Jack Riley later commented that Doc Dockery was “the most wounded person I have ever seen who lived.” There was perhaps no man who fought in the Battle of Getlin’s Corner who was more deserving of formal recognition for his bravery than was Charles “Doc” Dockery, but a Purple Heart was the only recognition he would receive. To the Marines of Getlin’s Corner, however, Doc Dockery’s selfless courage throughout the entire battle will live in their memories forever.

And then there was 2nd Lt. John Bobo, (Medal of Honor) whose weapons platoon had remained in support of the CP when the rifle platoons departed for their ambush locations. As the enemy attack quickly intensified, Lt. Bobo moved about the hill from one fighting position to another, encouraging his men and directing their fire into the spearhead of the enemy attack. When a mortar round severed his leg below the knee, Lt. Bobo never stopped, even for a minute, fighting tenaciously in spite of his devastating wound. As Top Rogers continued to move from one Marine position to the another, he eventually made his way to Lt. Bobo’s side and prepared to evacuate the young lieutenant. Bobo would have none of it. Bobo then ordered the 1st Sergeant to drag him to a more suitable fighting position.

Shortly after the 1st Sergeant left the lieutenant to continue his movements among the Marines’ fighting positions, Doc Braun made his way to Lt. Bobo’s side. In an effort to stem the bleeding, Doc Braun used a web belt around the severed leg. As Top Rogers had done before him, Doc encouraged the lieutenant to allow himself to be evacuated, but again Bobo would have none of it. Instead, he ordered the corpsman to drag him to yet another firing position where Bobo drove the stump of his leg into the dirt so he could further stem the bleeding and continue to fight. While he and Doc Braun lay side-by-side, firing at the advancing enemy, they were both raked by AK-47 fire, hitting the corpsman three times and killing the courageous young lieutenant.

Shortly after the 1st Sergeant left the lieutenant to continue his movements among the Marines’ fighting positions, Doc Braun made his way to Lt. Bobo’s side. In an effort to stem the bleeding, Doc Braun used a web belt around the severed leg. As Top Rogers had done before him, Doc encouraged the lieutenant to allow himself to be evacuated, but again Bobo would have none of it. Instead, he ordered the corpsman to drag him to yet another firing position where Bobo drove the stump of his leg into the dirt so he could further stem the bleeding and continue to fight. While he and Doc Braun lay side-by-side, firing at the advancing enemy, they were both raked by AK-47 fire, hitting the corpsman three times and killing the courageous young lieutenant.

As the CP Marines repulsed attack after determined attack, Lt. Prickett, realizing the urgency of the situation on Hill 70, turned his platoon around, and moved quickly back to the trail junction. Lieutenants Pultz, Neal, and Prickett quickly decided that Prickett would attack in the direction of the CP. Pultz and one of his squad leaders, Corporal Roger Turnquist, would then establish a blocking ambush to protect Prickett’s platoon from an attack from its rear, and to prevent the NVA from a flanking attack on Hill 70. With Turnquist’s squad in place, Lt Prickett’s platoon got on line to attack in the direction of the CP.

The lieutenants’ hastily conceived battle plan was a good one. Shortly after Prickett’s platoon had gotten on line to advance toward Hill 70, the NVA launched an attack from Prickett’s rear that was broken by Pultz and Turnquist. There would be plenty to contend with ahead of Prickett’s attacking platoon, and it was fortunate that the ambush had prevented the NVA from seriously complicating the entire situation with either an attack to the rear of the 1st platoon, or a flanking attack on the desperate Marines on Hill 70.

Exceptional heroism was not limited to the Marines in the CP on that day.

While Pultz and Turnquist remained at their ambush site for a brief time after they had blunted the NVA attack, Pultz put his Marines on line with orders to join Prickett’s platoon in its advance to Hill 70. That was no small effort, however, because the NVA pelted Pultz and his men as they advanced across an open area in their attempt to join with the 1st. Platoon.

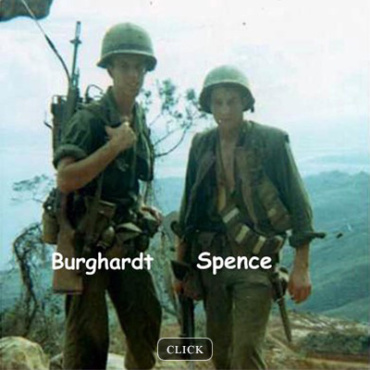

Meanwhile, while Lt. Prickett was leading his platoon toward Hill 70, he was struck down by a 30-caliber, wheel-mounted machine gun. His radioman, Lance Corporal Jim Burghardt, (Silver Star) saw the severity of the lieutenant’s wounds, and immediately began to drag him to a more protected area. As the enemy fire intensified, the lieutenant was seriously wounded a second time. At that point, L/CPL. Burghardt threw himself on top of the lieutenant to protect him from the withering machine gun fire. At one point, with Lt. Prickett’s .45 pistol in hand, L/Cpl. Burghardt was shot in the neck as he rose to fire at and kill an enemy soldier who was not more than five feet away.

With Lt. Prickett critically wounded, Lt. Neal assumed command of the platoon, immediately calling up a rocket team to take out the wheel-mounted machine gun that was making further progress impossible. (Many years later in his memoir, What Now Lieutenant?, four-star General Butch Neal would reflect on this moment and the hours that followed as the first time he truly understood “…the power and responsibility of leadership and command. It was daunting.”)

With the NVA machine gun no longer a factor, Neal relentlessly and skillfully continued to direct the 1st. Platoon’s attack until the Marines were finally able to break through the enemy resistance and join forces with the CP. As fighting continued to rage all over Hill 70, Lt. Neal assume command of the company at approximately 5:00 PM, established a defensive perimeter, and continued to beat back the NVA’s relentless attack.

As Lt. Neal took command of the company, he quickly relieved the seriously wounded First Sergeant who was attempting to coordinate close air support from two Marine helicopters entered the battle at a critical time. With devastating consequence to the enemy, Lt. Neal coordinated the close air support from Marine helicopter squadron VMO-2. The flight of two helicopter gunships, with the call sign “Deadlock Playboy”, was under the command of flight leader Captain Chris Bradley. His wingman was 1st. Lieutenant David Nazarian, and the two Marine pilots decimated the enemy force as its troops were regrouping for a final assault on the CP.

Lance Corporal Randy Plumley, who was still hog-tied and being guarded by an NVA soldier, recalled in amazement how the skillful pilots made three staffing runs against the NVA, pulling off from each run just feet from his position. After the third run, the soldier guarding Plumley beat a hasty retreat for cover, leaving Plumley alone on the side of Hill 70. Decades later when attorney Plumbley was serving as the District Attorney in Riverside, CA, he spoke with Chris Bradley for the first time. When Randy asked Chris how he was able to so skillfully stop firing just short of Plumley’s position, Bradley confessed that “God’s finger must have been on the trigger.” because the gunship pilot never even saw the lance corporal tied-up on the side of the hill.

With each Marine down to no more than 20 rounds of ammunition, one more concentrated attack on their position would likely have resulted in the total destruction of what remained of the CP and all the other Marines who were on Hill 70. Although the helicopter attacks had broken the back of the NVA effort to mount a final assault on the CP, individual NVA soldiers were still on and around Hill 70. Although Lt. Neal had organized a loose defensive perimeter as darkness fell over the battle field, several wounded Marines were alone or in small groups and outside of the relative safety of the perimeter. In their best English, NVA troops were calling “Corpsman up” hoping to draw Marines and Corpsmen out to answer the call and be ambushed in the process.

When total darkness finally enveloped Hill 70, it did not bring with it any rest for the embattled Marines, because there were still several wounded men in positions all around Hill 70. Jack Riley, realizing that one of those missing Marines was his own squad member, Pasquale Gigliotte, requested permission from Lt. Pultz to search for his squad member.

When total darkness finally enveloped Hill 70, it did not bring with it any rest for the embattled Marines, because there were still several wounded men in positions all around Hill 70. Jack Riley, realizing that one of those missing Marines was his own squad member, Pasquale Gigliotte, requested permission from Lt. Pultz to search for his squad member.

Riley had been wounded three times by this point. Lt. Pultz, seeing Riley’s condition and the obvious danger in allowing a single Marine to go in search of his fallen brothers, refused the request. The situation over the entire hill was extremely intense: wounded Marines were on their radios calling for help; nobody knew exactly where they were all located; Lt. Neal, concerned that another NVA attack of the CP could come at any moment, was focused on establishing a secure perimeter; the critically wounded had to be evacuated; darkness and the thick foliage limited visibility to no more than a foot or two.

With no orders issued—they didn’t need to be—Marine initiative and overwhelming concern dictated what had to be done at that point. Lt. Pultz, Corporal Paul Plouffe, and Sgt. Oscar Meeks gathered fellow Marines, and the three teams fanned out over Hill 70 in search of the dead and wounded. Darkness had completely enveloped the hill by this time. With tens of dozens of fallen warriors from both side strewn over the battle field, the tall grass and darkness made it impossible to distinguish a Marine from an NVA soldier without feeling blindly for any sort of identification. The boots Marines wore was a sure way of identification, and the search teams found themselves having to feel for footwear in order too distinguish between a Marine and an NVA soldier. The courage required by the men on those teams to complete their search and rescue missions—with a couple of teams going out two or three times—should not go unrecognized. In the complete darkness, with very little ammunition, and with no indication that the NVA would not resume their attack on the CP, these Marines were certain of only one thing: isolated in their search for their fallen brothers, they knew that another NVA attack would not likely be survivable.

As the teams returned to the defensive perimeter, Jack Riley was relieved to see Lt. Pultz return to the CP with Top Rogers, two other Marines, and Pasquale Gigliotti. Gig had his arm draped around the lieutenant’s shoulder for support. Gig’s massive leg-wound made it impossible to support his own weight.

As the teams returned to the defensive perimeter, Jack Riley was relieved to see Lt. Pultz return to the CP with Top Rogers, two other Marines, and Pasquale Gigliotti. Gig had his arm draped around the lieutenant’s shoulder for support. Gig’s massive leg-wound made it impossible to support his own weight.

Lt. Neal continued to consolidate the Marine positions, determine what munitions were available to defend against another attack, and to evaluate Marine casualties. It was now critical for the severely wounded to receive immediate care that could only be provided through hospital facilities. To that requirement, Neal ordered Lt. Pultz to coordinate a medevac (Medical Evacuation) of the most seriously wounded. The gravely wounded Marines would not survive the night without immediate medevac.

With no combat experience prior to Getlin’s Corner, and having never called in a medieval flight, even in a training exercise, Lt. Pultz was about to undergo serious, on-the-job-training—with lives very much in the balance. The challenge was made all the more difficult because it would have been too dangerous to illuminate the medevac landing zone (LZ) with flares, which is normally how an LZ is illuminated. Instead, C-4—an explosives that when lighted gives off a white-hot flame—was ignited and placed in inverted helmets to at least provide some visual references for the medieval pilots.

Further complicating the task of guiding the choppers to a safe landing, the LZ was considered “hot” (under enemy fire) and that required the helicopter to approach the LZ without its navigation light illuminated. That left Lt. Pultz with only one way to guide the medevac helicopters to its landing spot: he directed the pilot’s approached entirely from the sound of the chopper as it approached the LZ. So accurate were Pultz’s directions to the pilot—and with, no doubt, a little luck as well—that as he lay on the ground calling in the medevac, Pultz suddenly realized that helicopter was just feet away and headed for a landing directly on top of him. Had he not rolled out of the way at the last moment, there would surely have been another seriously injured Marine to load aboard the medevac. Once safely on the ground, Neal and Pultz were informed that the CH-34 medevac helicopter could only safely carry 8-9 wounded Marines. But the officers were determined to evacuate each of their critically wounded Marines, and in the end, all 15 of the most severely Marines were put onboard that night…..and they all survived!

At around 8:00 PM, with the evacuation of the 15 most severely wounded Marines and no further attacks on the CP, the Battle of Getlin’s Corner came to an end. As remarkable as was the battle itself, perhaps equally remarkable is the fact that all of the 47 Marines who required medical evaluation survived their wounds.

Despite being outnumbered three to one, by early morning on the 31st of March, the NVA division had disappeared into the countryside, leaving scores of their dead comrades on the battlefield.

In no other battle of such short duration in the history of the Marine Corps have the nation’s two highest decorations for valor been awarded to the men who fought in it: four Navy Crosses and the Medal of Honor. The five Silver Stars that were awarded is the nation’s 3rd highest award for valor, and that makes the Battle of Getlin’s Corner all the more extraordinary.

In no other battle of such short duration in the history of the Marine Corps have the nation’s two highest decorations for valor been awarded to the men who fought in it: four Navy Crosses and the Medal of Honor. The five Silver Stars that were awarded is the nation’s 3rd highest award for valor, and that makes the Battle of Getlin’s Corner all the more extraordinary.

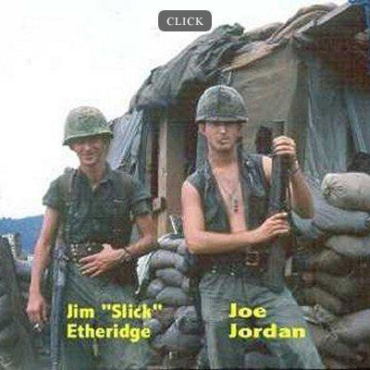

Reflecting on the Battle of Getlin’s Corner many years later, Lance Corporal Jim Etheridge of the 2nd Platoon reflected on battle: “I’m no hero, but I spent several hours around many of them that night. I relive that night over and over, as most of us who survived the battle do. I saw many of our brothers fall. Now, every year on 30 March, I hold a private vigil for them all by myself with candles and quietness. Then I lift a few beers for the ones who are gone now, and a few more for the rest of us.”

Semper Fidelus